Christian Art | George Herbert | The Temple | The Church | Avarice

George Herbert | The Temple | The Church | Avarice

Money, thou bane of blisse, and sourse of wo,

Whence com’st thou, that thou art so fresh and fine?

I know thy parentage is base and low:

Man found thee poore and dirtie in a mine.

Surely thou didst so little contribute

To this great kingdome, which thou now hast got,

That he was fain, when thou wert destitute,

To digge thee out of thy dark cave and grot:

Then forcing thee, by fire he made thee bright:

Nay, thou hast got the face of man; for we

Have with our stamp and seal transferr’d our right;

Thou art the man, and man but drosse to thee.

Man calleth thee his wealth, who made thee rich;

And while he digs out thee, falls in the ditch.

![]()

George Herbert | The Temple | The Church | Avarice

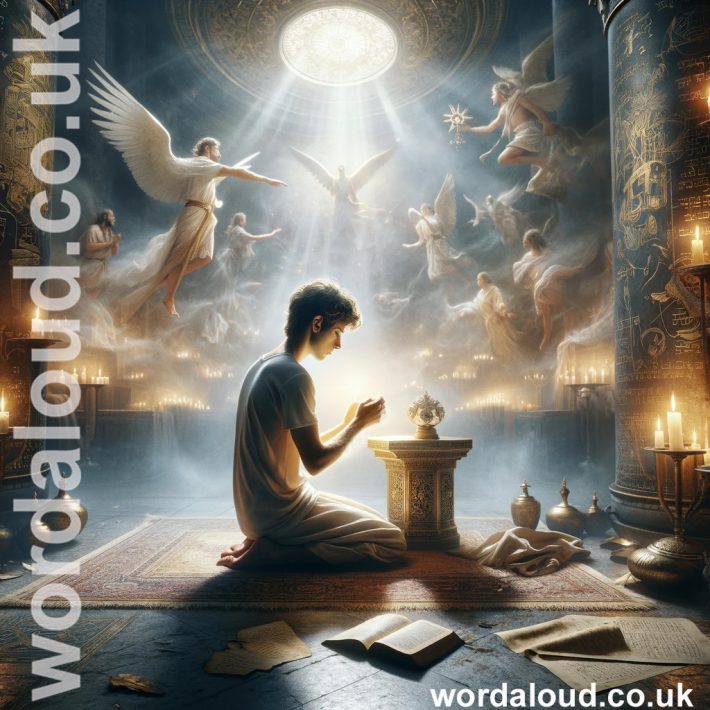

Herbert’s ‘Avarice’ critiques humanity’s obsession with wealth by tracing money’s journey from its origins to its corrupting influence on human values. The poem is structured as a meditation, moving from the origins of money to its transformation and eventual dominance over human life.

The opening lines establish money as a paradoxical force, both ‘bane of bliss’ and a ‘source of woe’ – ‘so fresh and fine’ and ‘base and low’. This ambivalence suggests that while money appears to offer benefits, its true nature is harmful. Herbert challenges the reader to consider money’s humble beginnings: it is ‘poor and dirty in a mine’. This image emphasizes a base materiality of money and origins in the earth, contrasting sharply with an elevated status humans later assign to it.

The refining process is described as an act of transformation by fire, where humans create value out of something that initially lacked it. The subsequent ‘stamp and seal’ is a crucial moment in the poem: humans impose their authority on money, projecting value onto it. Yet, in doing so, they unwittingly diminish themselves. The inversion of roles—money becomes ‘the man’, and man is reduced to ‘dross’—illustrates the corrupting effects of ‘Avarice’. The object gains power, while its creators lose their dignity and purpose.

Herbert concludes with a stark moral warning in the final couplet: that man, ‘While he digs out thee, falls in the ditch’. This image of falling into a ditch symbolizes spiritual ruin. It reflects futility and self-destruction inherent in humanity’s relentless pursuit of wealth. The poem suggests that by prioritizing money, humans neglect higher, spiritual concerns, effectively digging their own graves.

The poem employs clear, concrete imagery—mines, fire, stamps, and ditches—that grounds its critique in tangible processes. These physical actions highlight human effort behind money’s creation and the absurdity of its subsequent power over human lives. Herbert uses this imagery to draw attention to the artificiality of wealth’s value and the moral degradation it brings.

Theologically, ‘Avarice’ aligns with Herbert’s broader concern with idolatry. Money is treated as a false god, worshiped despite being a human creation. This misplaced reverence leads to a loss of spiritual priorities, with wealth supplanting God as the ultimate object of human devotion.

Herbert’s ‘Avarice’ offers a critique of greed, focusing on the self-inflicted harm caused by humanity’s elevation of wealth. It is not simply a condemnation of money but a reflection on the distortion of values that occurs when material gain takes precedence over spiritual and moral integrity.