Christian Art | John Donne | Holy Sonnets | Batter My Heart, Three-Personed God

John Donne | Holy Sonnets | Batter My Heart, Three-Personed God

Batter my heart, three-person’d God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp’d town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv’d, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov’d fain,

But am betroth’d unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

![]()

John Donne | Holy Sonnets | Batter My Heart, Three-Personed God

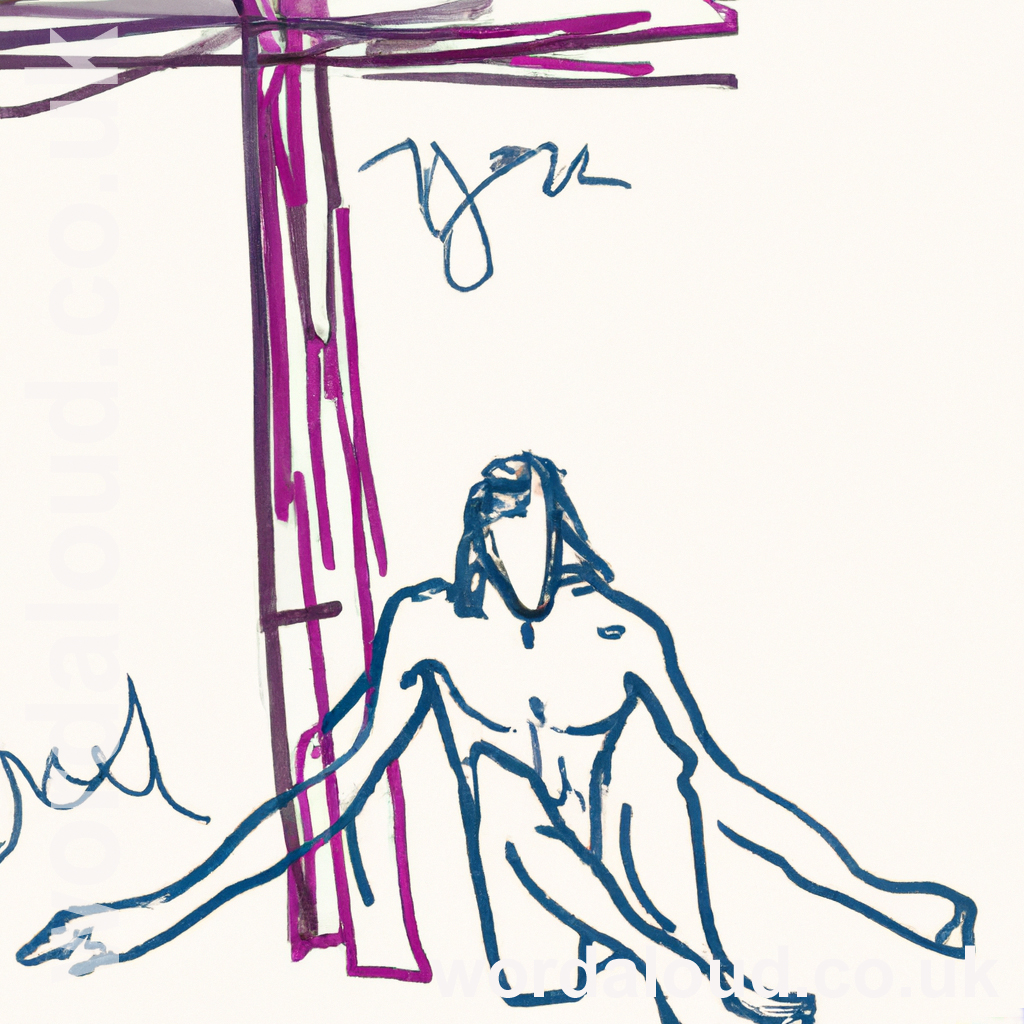

John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, beginning, ‘Batter my heart, three-person’d God,’ enacts a struggle between divine grace and human resistance, expressed through forceful imagery and paradox. The speaker does not ask for gentle persuasion but for a radical upheaval of the self. The poem presents a mind at war with itself, aware of divine sovereignty yet bound by sin, seeking liberation through subjugation.

The opening line calls on the ‘three-person’d God’—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—to ‘batter’ rather than merely shape the speaker’s heart. This violent verb contrasts with the more measured ‘knock, breathe, shine’, suggesting that God’s usual methods of persuasion have failed. The speaker’s heart must be forcefully taken, not won. Donne employs a sequence of destructive actions—’break, blow, burn’—that suggest refinement through suffering, recalling biblical images of fire and hammering as means of purification. The poet’s request is not for comfort but for obliteration and recreation, aligning with Christian notions of spiritual rebirth.

The metaphor of the self as a ‘usurp’d town’ deepens this conflict. The soul belongs to God but has been overtaken by an enemy—sin, Satan, or the corrupt will. The speaker ‘labors to admit’ God but finds himself powerless, reinforcing the doctrine of fallen humanity’s incapacity for self-restoration. ‘Reason, your viceroy in me’ should defend the city but is ‘captiv’d’ and ineffective. This theological position aligns with Augustinian and Calvinist views on human depravity, where the will, corrupted by sin, cannot effect its own salvation.

The sestet shifts from the language of war to that of marriage and desire. The poet confesses love for God but is ‘betroth’d unto your enemy’, echoing biblical depictions of idolatry as spiritual adultery. The plea—’Divorce me, untie or break that knot’—suggests that redemption requires dissolution, a violent severing of sinful bonds. The language intensifies: ‘Take me to you, imprison me, for I / Except you enthrall me, never shall be free.’ The paradox of captivity as freedom reflects Christian teachings on obedience to God as the highest form of liberty. In Donne’s vision, salvation is not gentle persuasion but an overpowering seizure.

The final paradox—’Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me’—is among the most arresting in the poem. The verb ‘ravish’ carries dual connotations of divine rapture and forced possession. The speaker calls for an invasion of the soul, where consent alone is insufficient; God must act. The erotic imagery, common in Christian mysticism, suggests that union with the divine is all-consuming, beyond reason’s control.

Structurally, the poem follows the Petrarchan sonnet form, with an octave presenting the dilemma and a sestet offering resolution. Yet Donne subverts traditional sonnet logic. Instead of resolving the tension, the turn heightens it, moving from external conquest to internal surrender. The poem’s form mirrors its subject: an ordered structure grappling with chaotic emotion.

Donne’s theological position here resists easy categorization. The rejection of reason and the demand for divine force align with Calvinist notions of irresistible grace. Yet the poem’s urgency suggests the personal anguish of one who longs for transformation but fears what it demands. The poem does not merely depict conversion; it enacts it, forcing the reader into the speaker’s turmoil.

At its core, Holy Sonnet 14 presents salvation as violent disruption. The poet, bound by sin, cannot free himself and must be taken by force. Love and destruction, captivity and freedom, desire and fear collapse into one. The God he calls upon is not distant but imminent, ready to act. The poem does not end in peace but in paradox, capturing the intensity of a soul in crisis, demanding divine intervention at any cost.