Office Of Readings | Friday, Lent Week 3 | Pope Saint Gregory The Great’s Reflection On Job And Christ | Christology | Ecclesiology

‘The mystery of our being made alive.’

Commentary On Pope Saint Gregory The Great’s Reflection On Job And Christ

As Pope from 590 to 604, Pope Saint Gregory the Great (c. 540–604) led the Church during a time of great upheaval, marked by political instability, the collapse of Roman infrastructure, and the threat of barbarian invasions.

Gregory’s interpretation of Job is deeply Christological and ecclesiological, meaning he sees Job as both a prefiguration of Christ and a representation of the Church. His exegesis follows the tradition of allegorical and moral interpretation that was common among the early Church Fathers, reading Scripture not only as historical narrative but as a living spiritual reality that speaks directly to the Christian experience.

Job As A Type Of Christ And The Church

A striking aspect of Gregory’s reflection is his presentation of Job as a figure of Christ. Job, though innocent, suffers greatly, just as Christ, the truly sinless one, endures suffering and death for the salvation of the world. Gregory makes a direct connection between Job’s words—’I have suffered this without sin on my hands, for my prayer to God was pure’—and Christ’s Passion. The reference to Christ’s hands being without sin recalls 1 Peter 2:22: ‘He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth.’

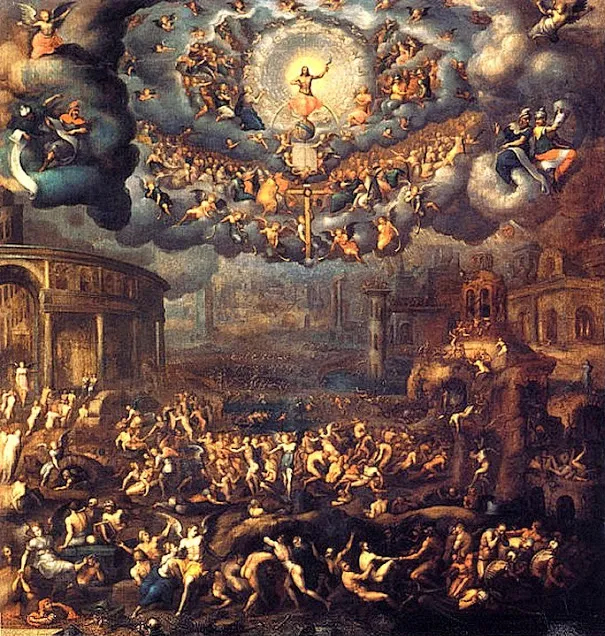

By extension, Job is a symbol of the Church, the Body of Christ. The suffering of Job represents the trials and tribulations of Christians, who must share in the sufferings of their head, Christ. Just as Job remains faithful amid his afflictions, so too must the Church persevere through persecution, temptation, and hardship. This is an important theme in Gregory’s pastoral writings, as he often reminded his clergy and flock that suffering is not meaningless but a participation in Christ’s redemptive work.

Power Of Intercessory Prayer

A key moment in this passage is Gregory’s emphasis on the purity of Christ’s prayer: ‘His prayer to God was pure, his alone out of all mankind, for in the midst of his suffering he prayed for his persecutors: ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’’ (Luke 23:34) This is the ultimate model of selfless, intercessory prayer, where Christ, instead of condemning his executioners, asks for their forgiveness.

Gregory sees in this the transformative power of prayer, which not only expresses mercy but also has the power to bring about conversion. The very people who crucified Christ—Roman soldiers, Jewish leaders, and bystanders—later came to recognize him as the Son of God. This echoes Saint Stephen’s martyrdom in Acts 7:60, where his final prayer for his persecutors precedes the conversion of Saul (who became Saint Paul).

Gregory’s pastoral theology frequently emphasized prayer as the lifeblood of the Church. In his Pastoral Rule, he stressed the necessity of prayer for bishops, priests, and all believers, urging them to intercede not only for themselves but also for their enemies. In this way, Gregory’s words remain profoundly relevant for modern Christians, calling Christians to imitate Christ’s radical forgiveness and to pray for those who oppose them.

Blood Of Christ | Atonement And Redemption

Gregory turns to the theme of Christ’s blood, drawing a powerful contrast with the blood of Abel. In Genesis 4:10, God tells Cain: ‘The voice of your brother’s blood cries out to me from the earth.’ This cry is one of vengeance, demanding justice for Abel’s murder. However, in Hebrews 12:24, we are told that Christ’s blood ‘speaks a better word than the blood of Abel’. Unlike Abel’s blood, which calls for retribution, Christ’s blood calls for mercy and salvation.

Gregory develops this theme by saying: ‘The blood that is drunk, the blood of redemption, is itself the cry of our Redeemer.’ This directly connects to the Eucharist, in which the faithful partake of the blood of Christ as the price of their redemption. The phrase ‘Earth, do not cover over my blood’ is interpreted in an ecclesial sense—meaning that the Church must not keep silent about the mystery of salvation but proclaim it to the whole world.

The universality of this message is crucial. Gregory, as a missionary Pope, sent Saint Augustine of Canterbury to evangelize the Anglo-Saxons, believing that the message of Christ’s blood and redemption was meant for all peoples, not just those within the Roman Empire. Today, his words challenge modern believers to be unafraid in proclaiming the Gospel, ensuring that Christ’s cry of salvation is not ‘hidden’ but made known to all.

Preaching And Witnessing To Christ

Gregory concludes by emphasizing the duty of all Christians to bear witness to their faith: ‘If the sacrament of the Lord’s passion is to work its effect in us, we must imitate what we receive and proclaim to mankind what we revere.’ This highlights the deep link between faith and action. It is not enough to believe in Christ’s sacrifice; one must also live it out and proclaim it.

For Gregory, this was not merely theoretical. As Pope, he was deeply engaged in the care of the poor, the reform of the clergy, and the protection of Rome from invading forces. He saw preaching and charity as inseparable—faith must be demonstrated through works. His Homilies on the Gospels show his pastoral concern, as he frequently urged his listeners to live according to what they professed in the Creed.

This remains an urgent message today. In a world where Christianity is increasingly marginalized in many societies, believers are called to proclaim their faith not just in words but through acts of charity, forgiveness, and moral integrity.

Lenten Call To Holiness

Gregory’s reflection, set within the penitential season of Lent, offers profound insights into the Christian journey. Through Job, he presents suffering as a means of union with Christ. Through Christ’s prayer, he calls us to intercede for others, even our enemies. Through the shedding of Christ’s blood, he reminds us of the power of redemption. And through his exhortation to proclaim the faith, he challenges modern Christians to live authentically as witnesses of the Gospel.

Pope Saint Gregory The Great’s Reflection On Job And Christ

Holy Job is a type of the Church. At one time he speaks for the body, at another for the head. As he speaks of its members he is suddenly caught up to speak in the name of their head. So it is here, where he says: I have suffered this without sin on my hands, for my prayer to God was pure.

Christ suffered without sin on his hands, for he committed no sin and deceit was not found on his lips. Yet he suffered the pain of the cross for our redemption. His prayer to God was pure, his alone out of all mankind, for in the midst of his suffering he prayed for his persecutors: Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.

Is it possible to offer, or even to imagine, a purer kind of prayer than that which shows mercy to one’s torturers by making intercession for them? It was thanks to this kind of prayer that the frenzied persecutors who shed the blood of our Redeemer drank it afterwards in faith and proclaimed him to be the Son of God.

The text goes on fittingly to speak of Christ’s blood: Earth, do not cover over my blood, do not let my cry find a hiding place in you. When man sinned, God had said: Earth you are, and to earth you will return. Earth does not cover over the blood of our Redeemer, for every sinner, as he drinks the blood that is the price of his redemption, offers praise and thanksgiving, and to the best of his power makes that blood known to all around him.

Earth has not hidden away his blood, for holy Church has preached in every corner of the world the mystery of its redemption.

Notice what follows: Do not let my cry find a hiding place in you. The blood that is drunk, the blood of redemption, is itself the cry of our Redeemer. Paul speaks of the sprinkled blood that calls out more eloquently than Abel’s. Of Abel’s blood Scripture had written: The voice of your brother’s blood cries out to me from the earth. The blood of Jesus calls out more eloquently than Abel’s, for the blood of Abel asked for the death of Cain, the fratricide, while the blood of the Lord has asked for, and obtained, life for his persecutors.

If the sacrament of the Lord’s passion is to work its effect in us, we must imitate what we receive and proclaim to mankind what we revere. The cry of the Lord finds a hiding place in us if our lips fail to speak of this, though our hearts believe in it. So that his cry may not lie concealed in us it remains for us all, each in his own measure, to make known to those around us the mystery of our new life in Christ.