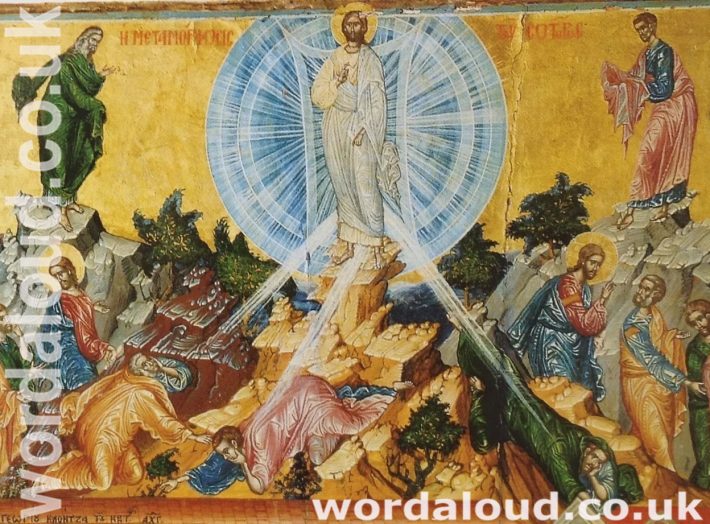

Christian Art | Jesus Christ | Transfiguration

Office Of Readings | Week 18, Thursday, Ordinary Time | From The Treatises Of Baldwin Of Canterbury | Love Is As Strong As Death | Jesus Christ Is King

‘Love is as strong as death.’

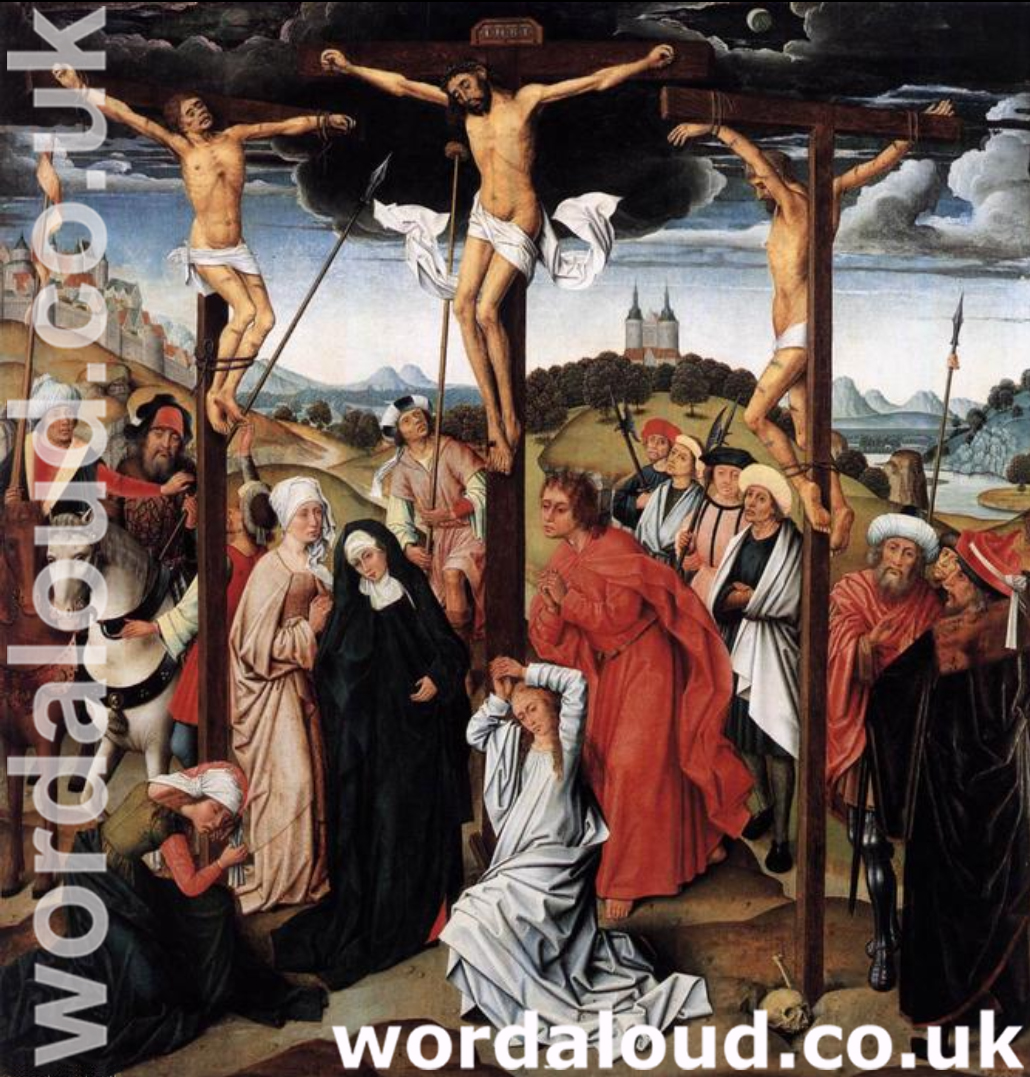

In this meditation, Baldwin of Canterbury reflects on the enduring biblical phrase ‘Love is as strong as death’ (Song of Songs 8:6), drawing a sharp and deliberate contrast between two forces — one that ends life, and one that restores it. Death, in Baldwin’s view, is not simply the end of physical existence, but the boundary that love refuses to accept. The passage reveals a deep confidence in Christ’s power not only to endure death but to reverse its finality.

Baldwin begins by acknowledging the brute power of death: it robs, despoils, and overcomes. No person can escape it. But love, he argues, is equal to death in strength — not because it avoids suffering, but because it passes through it and emerges with something greater. Love does not undo death by evasion, but by resurrection. This is not a general reflection on affection or human emotion, but a pointed theological claim about Christ’s love, which ‘is the death of death’.

This strong identification between Christ’s love and the destruction of death is rooted in scriptural language. Baldwin draws from 1 Corinthians 15:55 — ‘O death, where is your sting?’ — and combines it with imagery from the prophets and the Song of Songs. Christ’s resurrection is portrayed not only as a divine act of power, but as an act of love that reclaims what death thought it had secured.

Baldwin also describes a second kind of love — the love that believers show to Christ. This love is not passive admiration, but something demanding. It calls for the death of the old self: the ‘extinction of our old life’ and the ‘abolition of vice’. In this way, the love of Christ initiates a spiritual death, one that mirrors his own physical death, but with the promise of newness rather than loss. Believers are invited into a transformation of identity — to be ‘moulded to his image’ and to ‘put off the likeness of the earthly’.

The metaphor of the seal is central here. Baldwin interprets the biblical call — ‘Set me as a seal on your heart’ — as an appeal for internalisation. Christ’s love must leave its mark on the believer’s heart, shaping memory, desire, and conscience. The seal is not decorative; it is formative. It marks ownership, intimacy, and transformation. This reflects a strong tradition within medieval spirituality that the heart is the true dwelling-place of God and the centre of the person.

Baldwin’s voice then turns to prayer. He addresses God directly, asking for the removal of the ‘heart of stone’ and the gift of a ‘heart of flesh’ — a clear echo of Ezekiel 36:26. The prayer acknowledges the human need for divine reshaping: that the heart might not only be changed, but filled, claimed, and conformed to God’s own likeness. The prayer is not emotional display but theological expression — it asks for the very thing Baldwin has been describing: a life restored by love, remade by Christ’s image.

The overall structure of the piece moves from contrast (death vs. love), through explanation (Christ’s love defeats death), to imitation (believers die to sin), and finally to prayer (asking for the heart to be transformed). It reflects a typical movement in medieval spiritual writing — from theology, to ethics, to devotion — and aims to form the reader’s understanding, conscience, and desire all at once.

This short treatise carries echoes of other medieval authors, especially Bernard of Clairvaux, whose sermons on the Song of Songs also emphasise love as the soul’s journey into union with Christ. Like Bernard, Baldwin does not separate theology from affection. For him, doctrine leads to devotion, and love is not merely a subject to understand but a power to receive and return.

Baldwin’s reflection is both personal and theological. It invites the reader to consider the claim that Christ’s love is not an abstract force but a personal encounter that changes everything — even the meaning of death. In the end, death may still come, but it is no longer final. For those sealed by Christ’s love, it is the passage not to loss, but to life.

From The Treatises Of Baldwin Of Canterbury | Love Is As Strong As Death | Jesus Christ Is King

Death is strong: it has the power to deprive us of the gift of life. Love is strong: it has the power to restore us to the exercise of a better life.

Death is strong, strong enough to despoil us of this body of ours. Love is strong, strong enough to rob death of its spoils and restore them to us.

Death is strong; for no man can resist it. Love is strong; for it can triumph over death, can blunt its sting, counter its onslaught and overturn its victory. A time will come when death will be trampled underfoot; when it will be said: ‘Death, where is your sting? Death, where is your attack?’

‘Love is strong as death,’ since Christ’s love is the death of death. For this reason he says: ‘Death, I shall be your death; hell, I shall grip you fast.’ The love, too, with which Christ is loved by us is itself strong as death, since it is a kind of death, being the extinction of our old life, the abolition of vice, and the putting aside of dead works.

This love of ours for Christ is a sort of return, though not equal to his love for us; and it is a copy, a likeness of his. For he first loved us, and by the example of love that he sets before us, he has become a seal by which we are moulded to his image — putting off the likeness of the earthly and bearing that of the heavenly, loving him as we are loved. In this he leaves us an example, that we may follow in his footsteps.

That is why he says: ‘Set me as a seal on your heart.’ As though to say: Love me, as I love you; have me in your mind, in your memory, in your desire; in your sighing, your groaning, your weeping. Remember, man, in what state I fashioned you, how far I preferred you before the rest of creatures, the dignity with which I ennobled you; how I crowned you with glory and honour, made you a little less than the angels, and subjected all things under your feet. Remember not only the great things I did for you, but what harsh indignities I bore on your behalf; and see if you are not acting wickedly against me, if you do not love me. For who loves you as I love you? Who created you, if not I? Who redeemed you, if not I?

Lord, take away from me the heart of stone, a heart shrunken and uncircumcised — take it away and give me a new heart, a heart of flesh, a clean heart. You cleanse our heart and love the heart that is clean — possess my heart and dwell in it, both holding it and filling it. You surpass what is highest in me, and yet are within my inmost self! Pattern of beauty and seal of holiness, mould my heart in your likeness: mould my heart under your mercy, God of my heart and God my portion for ever. Amen.

Christian Prayer With Jesus Christ

Lord Jesus Christ,

you loved us even to the point of death,

and in rising, you robbed death of its hold.

Set your love as a seal upon our hearts:

that we may die to all that is false,

and live more deeply in your truth.

Teach us to love as you have loved us —

with patience, with courage,

with a heart that seeks no reward but your presence.

Shape our desires, our thoughts, and our will,

until they are conformed to yours.

Remove from us all that is hardened,

and give us hearts of flesh, ready to respond to your call.

In life and in death, may we be yours,

for you are our portion, our hope, and our joy,

now and to the end of the age. Amen.

Glossary Of Christian Terms

Baldwin of Canterbury

A 12th-century English theologian, monk, and Archbishop of Canterbury. He was known for his spiritual writings and his participation in the preaching of the Crusades. His Treatises reflect a deep concern with the moral and spiritual life.

Treatise

A formal written work dealing systematically with a subject. In medieval theology, treatises were often used to reflect on scripture or doctrine in depth.

‘Love is as strong as death’

A phrase from Song of Songs 8:6, often interpreted spiritually in Christian tradition to refer to the strength of divine love, particularly the love of Christ, which conquers even death.

Despoil

To strip or deprive someone of their possessions — in this context, death ‘despoils’ the human being of life and the body.

Seal (on the heart)

A biblical image from the Song of Songs, used here to represent the imprint or mark of divine love on the inner self. A seal connotes ownership, protection, and intimacy.

Old life / dead works

Expressions from the New Testament referring to the life shaped by sin or selfishness before conversion. ‘Dead works’ are deeds that are spiritually barren, disconnected from the life of God.

Heart of stone / heart of flesh

A scriptural image from Ezekiel 36:26, describing a transformation in which a person’s inner life is softened and made responsive to God. A heart of stone is closed, while a heart of flesh is open and living.

Vice

A habitual sin or moral failing — the opposite of virtue. In medieval Christian thought, vice must be overcome by grace and spiritual discipline.

Christ as the ‘death of death’

An idea drawn from Hosea 13:14 and 1 Corinthians 15, expressing the belief that Jesus’ death and resurrection nullify the finality of death for those united with him.

Portion

A biblical metaphor (see Psalm 73:26) meaning inheritance or source of satisfaction. When God is called ‘my portion,’ it expresses a relationship of total dependence and devotion.