‘Those who want to see into the depths must first consider the natural world, for knowledge of the Trinity is rightly compared to knowledge of the depths of the sea.’

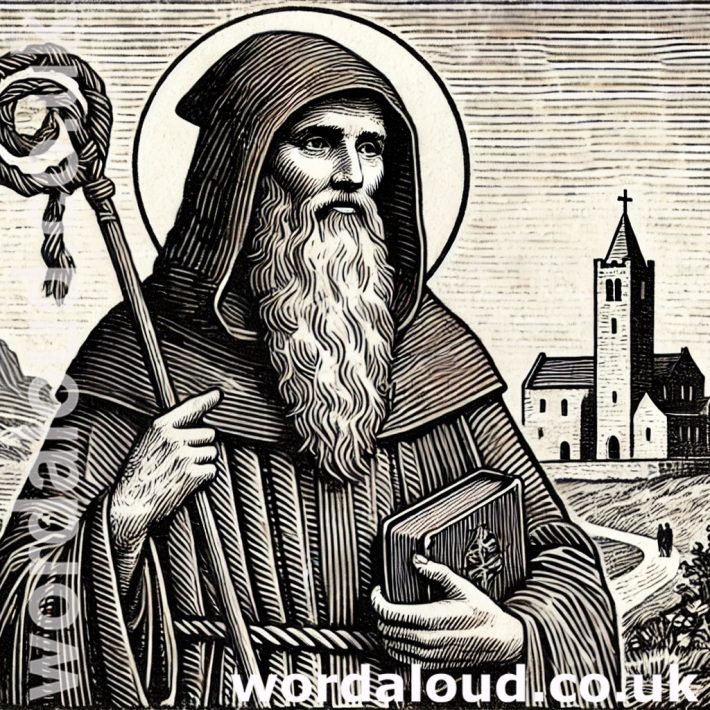

Saint Columbanus (c. 543–615) was an Irish missionary, monk, and writer, best known for founding monasteries across modern-day France, Switzerland, and Italy. Born in Leinster, Ireland, he became a monk at Bangor Abbey under Saint Comgall. Around 590, Columbanus and twelve companions set out as missionaries to continental Europe, where he established influential monasteries, including Luxeuil in France and Bobbio in Italy. His strict monastic rule emphasized asceticism, prayer, and manual labor.

A strong advocate for Irish monastic traditions, Columbanus sometimes clashed with local bishops and rulers. He was also a prolific writer, producing sermons, letters, and monastic rules. He spent his final years in Bobbio, where he died in 615. Today, he is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church, particularly as a patron of motorcyclists and against floods!

A Reading From The Instruction Of Saint Columbanus

God is everywhere. He is immeasurably vast and yet everywhere he is close at hand, as he himself bears witness: I am a God close at hand, and not a God who is distant. It is not a God who is far away that we are seeking, since (if we deserve it) he is within us. For he lives in us as the soul lives in the body – if only we are healthy limbs of his, if we are dead to sin. Then indeed he lives within us, he who has said: And I will live in them and walk among them. If we are worthy for him to be in us then in truth he gives us life, makes us his living limbs. As Saint Paul says, In him we live and move and have our being.

Given his indescribable and incomprehensible essence, who will explore the Most High? Who can examine the depths of God? Who will take pride in knowing the infinite God who fills all things and surrounds all things, who pervades all things and transcends all things, who takes possession of all things but is not himself possessed by anything? The infinite God whom no-one has seen as he is? Therefore let no-one try to penetrate the secrets of God, what he was, how he was, who he was. These things cannot be described, examined, explored. Simply – simply but strongly – believe that God is as God was, that God will be as God has always been, for God cannot be changed.

So who is God? God is the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, one God. Do not demand to know more of God. Those who want to see into the depths must first consider the natural world, for knowledge of the Trinity is rightly compared to knowledge of the depths of the sea: as Ecclesiastes says, And the great depths, who shall fathom them? Just as the depths of the sea are invisible to human sight, so the godhead of the Trinity is beyond human sense and understanding. Thus, I say, if anyone wants to know what he should believe, let him not think that he will understand better through speech than through belief: if he does that, the wisdom of God will be further from him than before.

Therefore, seek the highest knowledge not by words and arguments but by perfect and right action. Not with the tongue, gathering arguments from God-free theories, but by faith, which proceeds from purity and simplicity of heart. If you seek the ineffable by means of argument, it will be further from you than it was before; if you seek it by faith, wisdom will be in her proper place at the gateway to knowledge, and you will see her there, at least in part. Wisdom is in a certain sense attained when you believe in the invisible without first demanding to understand it. God must be believed in as he is, that is, as being invisible; even though he can be partly seen by a pure heart.

![]()