Christian Art | Ascension | Our Christian Ascent With Jesus To Heaven

Office Of Readings | Eastertide, Ascension | A Reading From The Sermons Of Saint Augustine | No-One Has Ascended Into Heaven But He Who Descended From Heaven

‘No-one has ascended into heaven but he who descended from heaven.’

A Heavenly Calling | Setting Our Hearts Above

Saint Augustine opens with an exhortation to elevate our hearts: ‘Let our hearts ascend with him.’ Drawing from Colossians 3:1-2, he calls Christians to turn inward and upward—to orient the whole self toward heavenly things, not earthly distractions. This is not an abstract mystical piety, but a profound participation in Christ’s own heavenly life.

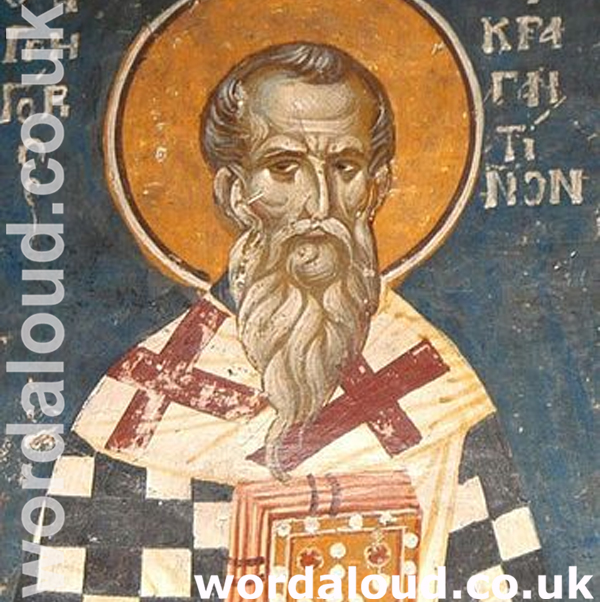

This spiritual ascent echoes a recurring theme in Christian mysticism, particularly in figures like Bernard of Clairvaux and Gregory of Nyssa, who describe the soul’s journey as a gradual ‘ascent to God’ through love and detachment. Augustine lays the groundwork for this ascent in faith, hope, and love, the theological virtues that root us in heaven even while our feet remain on earth.

Union With Christ | Ascension As Our Own Destiny

One of Augustine’s most striking assertions is that we are already in heaven with Christ. He writes: ‘He is there as our head; we are here as his body, and yet we are also there in him.’ This reveals his understanding of the mystical Body of Christ, drawn from 1 Corinthians 12:12 and Romans 12:5.

Here, Augustine is not being metaphorical—he is describing a spiritual reality: that Christ’s Ascension is not merely his personal triumph but the exaltation of all humanity. This echoes the teaching of Pope Leo the Great, who said, ‘The glorification of Christ is our elevation.’

This theological point is deepened by the scriptural phrase in Ephesians 2:6: ‘He raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus.’ Through baptism and the indwelling Spirit, we are already united to the glorified Christ and assured of sharing in his destiny.

Suffering With Christ | The Ascended Lord Still Suffers

Augustine profoundly reflects on Christ’s compassion by quoting the risen Lord: ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ (Acts 9:4) and ‘I was hungry and you gave me food’ (Matt. 25:35). This illustrates how the Ascended Christ is still in solidarity with his suffering members.

This paradox—that Christ is in glory and yet still suffers—underscores the mysterious unity of the Head and the Body. Even in exaltation, Christ does not distance himself from our afflictions. As Hebrews 4:15 affirms, ‘we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses.’

Theologically, this is Augustine’s affirmation that Christ’s divine presence remains active and compassionate on earth. This belief anchors Christian hope in the midst of suffering: our pain is never unnoticed by the glorified Lord.

Theology Of Presence | ‘He Did Not Leave Heaven When He Came Down To Us…’

One of the more theologically rich lines in the sermon is this: ‘He did not leave heaven when he came down to us; nor did he withdraw from us when he went up again into heaven.’ This echoes the Chalcedonian doctrine of Christ’s two natures: his divinity remains omnipresent, even as his humanity ascends.

This teaching finds resonance in Thomas Aquinas, who states that Christ’s bodily Ascension does not mean his absence, but a new mode of presence. As Pope Benedict XVI observed, ‘Jesus’ Ascension is not a departure into some distant place in the cosmos but rather a stepping into the mystery of God.’

Liturgically, this is captured in the Preface of the Ascension in the Roman Missal:

‘He ascended, not to distance himself from our lowly state but that we, his members, might be confident of following where he, our Head and Founder, has gone before.’

Mystical Union | ‘No One Ascended Except Christ—And We Are In Him’

Augustine meditates deeply on John 3:13: ‘No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven.’ He unpacks this in terms of our mystical union with Christ: ‘He is our head; we are his body.’

This identification with Christ—the Church as Christ in the plural, as it were—is a central theme in Augustine’s theology. Christ is not merely an individual; he is the Totus Christus (the whole Christ): Head and members united.

This idea is echoed in the Eastern Fathers, such as Athanasius: ‘God became man so that man might become god.’ Augustine’s view complements this, not by confusing natures, but by affirming that grace unites us to the divine Sonship through the Spirit.

Ascension As Mission And Hope

Augustine’s sermon subtly anticipates the missionary implication of the Ascension. The Lord ascends not to abandon the world, but to send the Spirit—the Paraclete who empowers the Church’s witness.

In modern theology, especially in Pope Francis’s Evangelii Gaudium, the Ascension is connected to the mission of the Church: to proclaim the gospel, confident in the presence of the risen and ascended Christ. Augustine helps us see that evangelization is grounded in communion with the exalted Lord.

The Ascension also grounds Christian eschatology—our ultimate hope. As Gaudium et Spes (Vatican II) reminds us, ‘Christ, who was raised from the dead and ascended into heaven, is the principle and source of our future resurrection.’ We look not to escape this world, but to see it transformed in Christ.

A Reading From The Sermons Of Saint Augustine | No-One Has Ascended Into Heaven But He Who Descended From Heaven

Today our Lord Jesus Christ ascended into heaven; let our hearts ascend with him. Listen to the words of the Apostle: If you have risen with Christ, set your hearts on the things that are above where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God; seek the things that are above, not the things that are on earth. For just as he remained with us even after his ascension, so we too are already in heaven with him, even though what is promised us has not yet been fulfilled in our bodies.

Christ is now exalted above the heavens, but he still suffers on earth all the pain that we, the members of his body, have to bear. He showed this when he cried out from above: Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? and when he said: I was hungry and you gave me food.

Why do we on earth not strive to find rest with him in heaven even now, through the faith, hope and love that unites us to him? While in heaven he is also with us; and we while on earth are with him. He is here with us by his divinity, his power and his love. We cannot be in heaven, as he is on earth, by divinity, but in him, we can be there by love.

He did not leave heaven when he came down to us; nor did he withdraw from us when he went up again into heaven. The fact that he was in heaven even while he was on earth is borne out by his own statement: No one has ever ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man, who is in heaven.

These words are explained by our oneness with Christ, for he is our head and we are his body. No one ascended into heaven except Christ because we also are Christ: he is the Son of Man by his union with us, and we by our union with him are the sons of God. So the Apostle says: Just as the human body, which has many members, is a unity, because all the different members make one body, so is it also with Christ. He too has many members, but one body.

Out of compassion for us he descended from heaven, and although he ascended alone, we also ascend, because we are in him by grace. Thus, no one but Christ descended and no one but Christ ascended; not because there is no distinction between the head and the body, but because the body as a unity cannot be separated from the head.

Glossary Of Terms

Ascension: The event, forty days after the Resurrection, in which Jesus was taken bodily into heaven in the presence of his disciples (Acts 1:9–11).

Theological Virtues: Faith, hope, and love—virtues infused by God into the souls of the faithful to enable them to act as his children and merit eternal life (cf. 1 Corinthians 13:13).

Mystical Body of Christ: A theological term describing the Church as united in Christ, who is the Head, and all believers as members (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:12–27).

Divinity: The divine nature or essence of God; referring to Jesus Christ’s full participation in the nature of God.

Solidarity: A sense of shared experience or suffering; in theology, it often refers to Christ’s continued union with humanity, especially in suffering.

Totus Christus (Latin: ‘the whole Christ’): A concept from Saint Augustine expressing the unity of Christ the Head with his Body, the Church.

Chalcedonian Doctrine: The definition from the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451) that Christ is one Person in two natures—fully God and fully man—without confusion or separation.

Mystical Union: The spiritual union of the believer with Christ, particularly through the sacraments and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

Liturgical Preface: The opening part of the Eucharistic Prayer in the Mass, often proper to a feast or season, giving thanks and recounting the significance of what is being celebrated.

Eschatology: The study of the ‘last things’ — death, judgment, heaven, and hell; often refers to Christian hope in the final fulfillment of God’s plan.

Evangelization: The act of proclaiming the Gospel; bringing the Good News of Jesus Christ to others in word and deed.

Paraclete: A name for the Holy Spirit meaning ‘Advocate’ or ‘Helper’ (John 14:16); the Spirit promised by Jesus after his Ascension.

Heavenly Session: A theological term for Christ’s current reign at the right hand of the Father following his Ascension (cf. Hebrews 1:3).

Unity of the Head and Body: The belief that Christ (the Head) and the Church (his Body) are inseparably united, both spiritually and mystically.

Prayer

Risen and Ascended Lord,

draw our hearts to you where you are seated in glory.

Let us not cling to the things below,

but set our minds on the hope above.

Though we still walk this earth,

help us live as citizens of heaven,

united to you in love,

strengthened by your Spirit,

and committed to your mission.

You did not ascend to leave us,

but to intercede for us,

and to prepare a place for us.

Teach us to live in the confidence

that where the Head has gone,

the Body will surely follow.

Amen.