John Donne | Holy Sonnets | What If This Present Were The World’s Last Night?

What if this present were the world’s last night?

Mark in my heart, O soul, where thou dost dwell,

The picture of Christ crucified, and tell

Whether his countenance can thee affright.

Tears in his eyes quench the amazing light;

Blood fills his frowns, which from his pierced head fell;

And can that tongue adjudge thee unto hell,

Which pray’d forgiveness for his foes’ fierce spite ?

No, no; but as in my idolatry I said to all my profane mistresses,

Beauty of pity, foulness only is

A sign of rigour ; so I say to thee,

To wicked spirits are horrid shapes assign’d;

This beauteous form assures a piteous mind.

![]()

John Donne | Holy Sonnets | What if this present were the world’s last night?

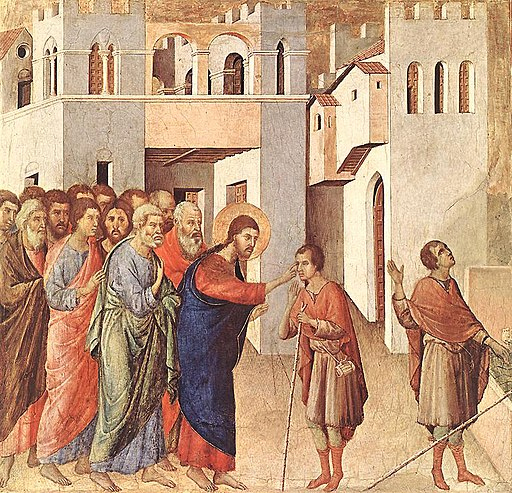

The poem confronts the possibility of the world’s last night, situating Donne in a moment of existential urgency. The question is not abstract but immediate: ‘What if this present were the world’s last night?’ Donne directs the soul inward, urging it to consider the image of Christ crucified and assess whether his suffering face inspires fear. The poem explores the contrast between divine justice and mercy, questioning whether judgment should be understood in terms of terror or compassion.

The first quatrain establishes the setting. Donne does not look to external signs but to the heart: ‘Mark in my heart, O soul, where thou dost dwell, / The picture of Christ crucified.’ The phrase ‘where thou dost dwell’ suggests that the soul’s location is not separate from Christ’s suffering but intimately connected to it. The instruction to ‘mark’ implies contemplation, an inward examination. The final phrase, ‘and tell / Whether His countenance can thee affright,’ introduces the key question: does the crucified Christ inspire fear?

The second quatrain deepens the imagery of Christ’s suffering. ‘Tears in His eyes quench the amazing light’ presents a paradox: Christ’s divine radiance is softened by sorrow. The ‘amazing light’ suggests divine glory, yet it is veiled by ‘tears’—a sign of Christ’s compassion. This is reinforced by ‘Blood fills His frowns, which from His pierced head fell.’ The image is both one of suffering and overwhelming sacrifice. The next lines pose the central theological question: ‘And can that tongue adjudge thee unto hell, / Which pray’d forgiveness for His foes’ fierce spite?’ The implied answer is no. The same voice that cried for mercy on behalf of His enemies is not one of condemnation but of salvation.

The third quatrain introduces a personal reflection. ‘No, no; but as in my idolatry / I said to all my profane mistresses, / Beauty of pity, foulness only is / A sign of rigour.’ Donne recalls a time when he equated outward beauty with mercy and ugliness with severity. This confession acknowledges a past error: Donne misunderstood appearances, attributing harshness to what was merely unattractive, and gentleness to what was appealing. This misjudgment is now recognized as flawed, providing a lens through which to re-examine Christ’s suffering. The crucifixion, which might appear terrifying, should not be confused with divine wrath.

The final couplet resolves the argument: ‘To wicked spirits are horrid shapes assign’d; / This beauteous form assures a piteous mind.’ The contrast is clear: the damned are given monstrous appearances, but Christ’s suffering is ‘beauteous’ because it reflects divine pity rather than vengeance. The conclusion draws the poem’s meditation toward assurance—Christ’s suffering face does not condemn but redeems.

The poem unfolds as a theological reflection that moves from fear to trust. Donne begins with the assumption that judgment should be terrifying but arrives at the realization that divine justice, as embodied in Christ, is inseparable from mercy. The image of Christ crucified, rather than a symbol of wrath, is a reassurance of love. The poet’s recognition of his past misconceptions parallels the soul’s journey from misunderstanding to faith.