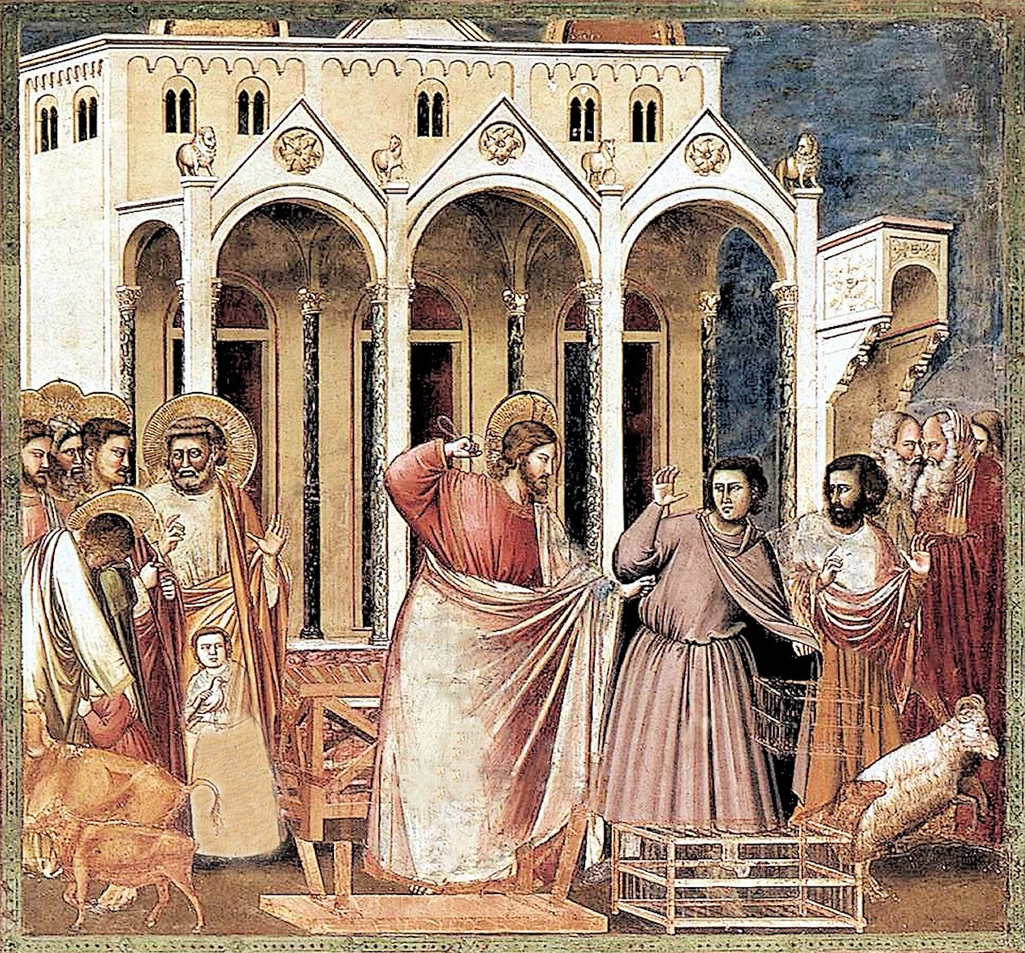

Christian Art | Parable Of The Pharisee And The Tax Collector

Luke 18: 9-14 | Week 3 Saturday Lent | Audio Bible KJV

9 And he spake this parable unto certain which trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and despised others:

10 Two men went up into the temple to pray; the one a Pharisee, and the other a publican.

11 The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican.

12 I fast twice in the week, I give tithes of all that I possess.

13 And the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to me a sinner.

14 I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other: for every one that exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.

This is among the most perfect of the parables to listen to during Lent – indeed, it has resonances that must extent to each and every time we receive the Eucharist. We are simply not worthy. And God’s mercy extends to us nonetheless.

The prayer of the Pharisee is false. It is not true prayer. We see him, standing there in the presence of God and congratulating himself, as if he does not need God for his redemption, as if he can redeem himself.

‘I do this, I do that, I do the other…’ As if he has bought his place in heaven though observance of the Law – the letter and not the spirit thereof.

The Pharisee shows his lack of love and humility before God, and too before his fellow human beings.

It is not so strange that people of Bible times, before and without the acceptance of Jesus’ teaching, would have considered the Pharisee the more justified before God. He is, perhaps, living his life as well as anyone could according to the Old Law alone. He is probably a ‘good man’, living as best as he knows how. This is one reason why Jesus’ message is so radical, and so dangerous: because this, justification by good works, is not enough; it is the publican who empties himself before God, and who gives himself utterly as a helpless sinner, begging mercy, who is justified. We may imagine that, in the light of the squabbles among the Jews and the dangerously disintegrating effects of sectarianism, Jesus is seeking to shock his listeners into a new and universal awareness of every man’s true, and only true, relationship with God, and so with himself and with his fellow man.

The parable reminds us of our own proper and true frame of mind as we approach Jesus. The publican, the tax collector, cannot see himself as able to approach God closely and remains afar off. For all his sins, he has humility. He cannot lift up his eyes to heaven. He knows that he is a sinner. He only offers God sincere repentance.

We remember this man when we are called to behold the Lamb of God.

Jesus teaches this parable to help us to have confidence to repent, to confess our sins, and to recognise that it is honesty about ourselves, and our relationship with God, that God most values. We are not here to show off to God; we are here to ask him for everything that we cannot do for ourselves, and to admit that, on our own, we cannot do so.

‘Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.’

![]()

Audio Bible KJV | Endnotes

The Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector is one of many parables told by Jesus to illustrate the importance of humility and the danger of self-righteousness.

In the parable, Jesus contrasts the attitudes of two men who went to the Temple to pray. One was a Pharisee, a member of a religious sect known for their strict adherence to the law and their sense of superiority over others. The other was a tax collector – in the KJV a ‘publican’ – a hated figure among the Jewish people because of their collaboration with the Roman occupiers.

The Pharisee prayed with great self-assurance, thanking God that he was not like other men, nor like the tax collector. He also listed his good deeds, such as fasting and giving tithes, as evidence of his righteousness. On the other hand, the tax collector, recognizing his sin and unworthiness, simply prayed: ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner.’

The parable teaches an important lesson for Christians, who are called to humility and self-awareness of their own sin, rather than boasting about our righteousness. As Jesus taught in his Sermon on the Mount: ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.’ (Matthew 5:3)

In the Christian tradition, the parable of The Pharisee and The Tax Collector is often associated with the larger theme of the Crucifixion of Jesus – the Christian Cross as sign of the redemption of humanity from sin. Through his death and Resurrection, Jesus brings salvation to the penitent – he who prays: ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner.’ Through such modesty, through becoming small, becoming as a child, we may receive the unmerited gift of eternal life in heaven, rather than condemnation to hell.

Baptism, Christian prayer, the celebration of the Passion of the Christ in Christian worship, recall us to the Cross, as to the glorified Christ the Redeemer. We are asked to pray with Jesus as it were in the Garden of Gethsemane. As Jesus taught in the Parable of the Prodigal Son, we are asked to humble ourselves and so be welcomed home.