Christian Art | Origen Of Alexandria

‘To pray is not to use many words, but to come to God with a devoted mind and a disposition formed by the desire for what is truly good.’

Origen Of Alexandria | Life, Theology, Controversy And Legacy

Origen of Alexandria, also known as Origen Adamantius, lived during a formative period of Christian thought in the Roman East. His life was shaped by early Christian devotion, intense scriptural study, pastoral work, ecclesiastical conflict, and the intellectual currents of Alexandria and Caesarea. Origen’s writings occupy an important place in the history of biblical interpretation and early Christian theology. At the same time, doctrines associated with his name became sources of dispute long after his death, influencing the Catholic Church’s decision that he be not a saint.

Life in Alexandria

Origen was born around 185 AD in Alexandria, a major centre of learning, commerce, and religious diversity in the Roman Empire. The Christian community in Alexandria had already developed institutions for teaching, including the Catechetical School, with which Origen later became closely associated. His father, Leonides, raised him in the Christian faith and encouraged rigorous study of Scripture. Early Christian accounts describe Leonides giving thanks for the boy’s devotion to biblical learning.

When Origen was about seventeen, his father was martyred during the persecution under the emperor Septimius Severus in 202 AD. His mother prevented him from attempting to share in his father’s martyrdom by hiding his clothes so that he could not leave the house. After his father’s death, Origen took responsibility for supporting his family by teaching grammar while continuing his own education.

Alexandria offered Origen access to a breadth of intellectual resources. Philosophical schools, Jewish scholarship and Christian teaching coexisted within the city. Origen likely studied under Clement of Alexandria and soon became involved in teaching Scripture to both Christian pupils and inquirers. His approach reflected the Alexandrian tradition of reading the Bible at multiple levels. In one homily he remarked: ‘The Scriptures are of little use to those who understand them as they are written.’ This statement illustrates Origen’s conviction that Scripture contained deeper spiritual meanings beyond the surface sense.

Teaching, Exegesis, And Early Writings

Origen’s work as a teacher in Alexandria expanded rapidly. His reputation for ascetic discipline and devotion drew students to him. He lived simply, fasted regularly, and devoted long hours to scriptural study. He taught grammar to support his household but placed his primary emphasis on the study of Scripture. Origen’s method involved engagement with the literal text, attention to language and historical context, and exploration of the spiritual dimension of Scripture.

It was during this period that he produced several early commentaries and homilies. Origen’s commentary on John and his exposition of the Song of Songs are among the earliest substantial Christian treatments of these texts. For Origen, the Song of Songs described the union between the soul and the Word of God, while John’s Gospel offered a profound expression of Christ’s nature and mission. Origen wrote of Scripture: ‘The Word of God is like the tree of life, offering fruit to those who can receive and shade to those who need rest.’

As his reputation grew, Origen was at times asked by foreign bishops to preach, even though he remained a layman. Such events later contributed to tensions with the bishop of Alexandria, Demetrius. These tensions reached a critical point when Origen was ordained a priest by bishops in Palestine during a visit to Caesarea. Demetrius disputed the validity of the ordination, asserting that it violated ecclesiastical order. A synod in Alexandria censured Origen and declared him ineligible for priestly office there.

The Caesarean Years And The Later Life

Following his conflict with Demetrius, Origen settled in Caesarea around 231–232 AD. He founded a new school for scriptural study, attracting students who included future bishops and scholars. In Caesarea he produced many of his most extensive works, including large sections of his commentaries and homilies, as well as the composition of On First Principles and the text-critical project known as the Hexapla.

The Hexapla was an immense undertaking. It presented the Old Testament in six parallel columns: the Hebrew text, the Hebrew transliterated into Greek, and four Greek translations (Aquila, Symmachus, the Septuagint, and Theodotion). This project aimed to clarify textual variations and preserve the integrity of the scriptural tradition. Origen compared Scripture to a fountain of continuous refreshment, writing: ‘Who is able to know the whole depth of the meaning of even a single phrase of Scripture? It is a well of living water.’

In Caesarea, Origen also produced apologetic and doctrinal works. His Contra Celsum responded to a detailed critique of Christianity by the philosopher Celsus. This work defended the rationality of Christian faith, addressed philosophical objections, and explained the coherence of Christian teaching. In its opening pages Origen wrote: ‘The Gospel has a power that convinces those who merely hear it, even before they give attention to the reasonings.’

Origen’s life in Caesarea ended during the Decian persecution. He was arrested, imprisoned, and tortured. According to ancient accounts, he was racked, stretched, and threatened with fire. Although eventually released, the injuries sustained during imprisonment weakened him. He died in Tyre around 253–254 AD. Reflecting elsewhere on the trials of believers, he wrote: ‘The power of God is made perfect in weakness, and the soul is proved by trials.’

Themes In Origen’s Theology

Origen’s theological reflections are collected most systematically in On First Principles. This work addresses God, creation, rational beings, free will, Scripture, and eschatology. Because it survives primarily in a Latin translation by Rufinus, and only partially in the original Greek, there has long been debate regarding which sections represent Origen’s own teaching and which may reflect later adaptations or interpolations.

The Trinity

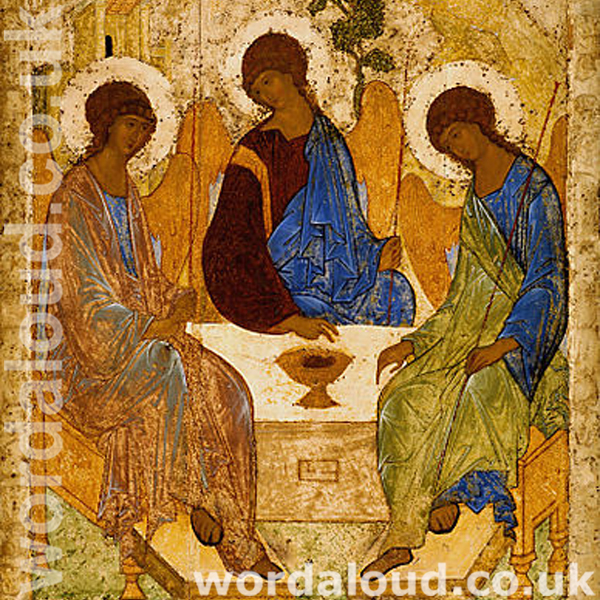

Origen taught that God the Father is the source or fountain of the Godhead, the Son is eternally begotten, and the Spirit proceeds from God. He wrote: ‘The Father is the fountain of the Godhead; the Son is the eternal radiance of His glory.’ Some of Origen’s language suggests distinctions within the Trinity that later interpreters viewed as subordinationist, though the vocabulary of his time did not yet employ the later Nicene terminology.

Creation And Rational Beings

Origen described rational beings as created with free will. In On First Principles he wrote: ‘Every rational soul is capable of both good and evil, and possesses free will.’ He also explored the idea of the pre-existence of souls. Some passages suggest that rational beings existed before their embodied life. This idea sought to explain moral diversity and the origins of human freedom. Later doctrinal formulations, especially in the West, did not adopt this view, and it became one of the issues associated with the Origenist controversies.

The Interpretation Of Scripture

Origen’s method of scriptural interpretation incorporated literal, moral, and spiritual senses. He wrote: ‘The Scriptures have a literal meaning, but also a moral meaning, and beyond these a spiritual meaning, revealed to those who have been purified by the Word.’ This approach shaped Christian exegesis for centuries, especially within monastic settings.

Eschatology And Restoration

Origen’s reflections on the end of all things emphasised God’s purpose to restore creation. In On First Principles he stated: ‘The end is always like the beginning,’ and ‘God, through His Christ, restores all things in whatever manner they have been arranged.’ Some later readers interpreted such statements as teaching a universal restoration in which all rational beings, including the devil, would eventually be reconciled to God. Whether Origen intended this as a necessary outcome or expressed hope grounded in divine goodness has long been debated. His writings also emphasise purification, judgement, and transformation.

Spirituality And Pastoral Teaching

Origen’s spirituality was shaped by ascetic discipline, prayer, and continual engagement with Scripture. He lived simply and urged others to unite action with prayer. In On Prayer he wrote: ‘He prays without ceasing who unites prayer with right action and right action with prayer.’ Origen viewed Scripture as a means through which Christ teaches and heals. A fragment from Origen’s homilies on Luke states: ‘Christ teaches and heals through the Scriptures; let the one who hears become like fertile ground.’

Origen’s homilies often integrate exposition of the text with guidance for Christian life. These writings influenced monastic and pastoral traditions, shaping the practice of lectio divina and the understanding of Scripture as a living word addressed to the believer.

The Origenist Controversies

The centuries following Origen’s death were marked by two major waves of controversy concerning doctrines associated with his teaching. These controversies shaped later perceptions of Origen and contributed significantly to the reasons he is not considered a saint by the Catholic Church.

Fourth-Century Disputes

In the late fourth and early fifth centuries, Origen’s writings were used widely in monastic communities in Palestine and Egypt. Some monks adopted speculative interpretations of his ideas, particularly regarding the pre-existence of souls and the nature of the resurrection. The result was conflict within monastic circles.

Figures such as Epiphanius of Salamis criticised Origen’s theology and opposed the use of his works. Jerome, who had earlier drawn deeply from Origen’s writings, later adopted a more hostile stance during these disputes. Rufinus of Aquileia defended Origen and argued that many controversial passages were later additions. This controversy created lasting divisions over Origen’s legacy.

Sixth-Century Condemnations

A second wave of controversy emerged in the sixth century. Emperor Justinian sought to eliminate doctrinal disputes within the empire and issued targeted condemnations of propositions associated with Origenism. Around 543 AD, a local synod in Constantinople condemned several teachings attributed to Origen, including:

- the pre-existence of souls;

- the eventual salvation of all rational creatures without exception;

- certain views of the resurrection;

- statements concerning the relation of the Son to the Father that appeared to imply subordination.

Scholars debate whether these anathemas were formally adopted by the Second Council of Constantinople in 553 AD. Regardless of their precise canonical status, they soon became linked with conciliar authority and shaped later ecclesiastical attitudes. By the early Middle Ages in the West, Origen’s name had become strongly associated with doctrinal error, even though many of the condemned propositions do not appear in the surviving Greek fragments of his works.

Why Origen Is Not Considered A Saint By The Catholic Church

Several factors contribute to the fact that Origen is not recognised as a saint in the Catholic Church. These reasons involve doctrinal concerns, textual uncertainty, canonical issues, and the development of liturgical veneration.

Association With Doctrinally Suspect Views

Doctrines connected with Origen’s name were later judged by the Church to be incompatible with established teaching. These include the pre-existence of souls, the possibility of universal restoration understood as a necessary outcome, and certain formulations regarding the Trinity. While debates continue regarding whether Origen personally held all the views later attributed to him, the association of these doctrines with his name created significant obstacles to his veneration.

Textual Instability of On First Principles

The main version of On First Principles was transmitted through Rufinus’s Latin translation. Rufinus stated that he corrected passages that he believed had been altered by opponents of Origen. Jerome claimed Rufinus had modified the text to make it appear more orthodox. This dispute created long-lasting uncertainty about Origen’s precise views, complicating efforts to assess his orthodoxy. Because canonisation requires clarity regarding a person’s fidelity to the faith, this textual confusion contributed to the absence of formal recognition.

The Sixth-Century Anathemas

The condemnations associated with the sixth-century Origenist controversy played a significant role. Even if the anathemas were directed at Origenist doctrines rather than Origen personally, they created a strong association between his name and doctrinal error. Later ecclesiastical writers and compilers of liturgical calendars rarely included individuals connected with condemned teachings.

Canonical Concerns Regarding Ordination

Ancient accounts describe Origen as having made himself a eunuch in his youth due to a literal reading of Matthew 19:12. Whether this account is historical remains uncertain, but if taken as fact, later canonical regulations would have regarded such an act as a barrier to ordination. Because Origen’s ordination was already contested in his own lifetime, and because canon law disqualified those who had mutilated themselves, this factor also influenced later hesitation about venerating him.

Lack of a Continuous Liturgical Cult

Early sainthood depended on local and continuous liturgical veneration. Origen did not develop a sustained cult in the West. Some communities in the East valued his spiritual writings, but the broader Church did not develop a tradition of liturgical celebration. Without such ongoing veneration, later canonisation did not occur.

Reception And Influence

Although not recognised as a saint, Origen’s influence on Christian thought is extensive. In the East, theologians such as Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa drew deeply from his work. Origen’s writings informed the development of monastic practices and biblical interpretation. In the West, Origen’s influence passed through figures such as Ambrose of Milan, Hilary of Poitiers, and Jerome, even when Jerome criticised Origen during later controversies. Medieval exegetical traditions, especially the fourfold sense of Scripture, reflect methods shaped by Origen and the Alexandrian school.

Modern scholarship has renewed interest in Origen through critical editions of his works and exploration of the historical context of his thought. Origen’s approach to Scripture, his reflections on prayer, and his desire to integrate philosophical inquiry with Christian faith continue to attract attention. In one of his homilies he wrote: ‘The soul is purified by following Christ, who is the Way, the Truth and the Life.’ This is a thought which expresses the practical and spiritual orientation that shaped Origen’s teaching.