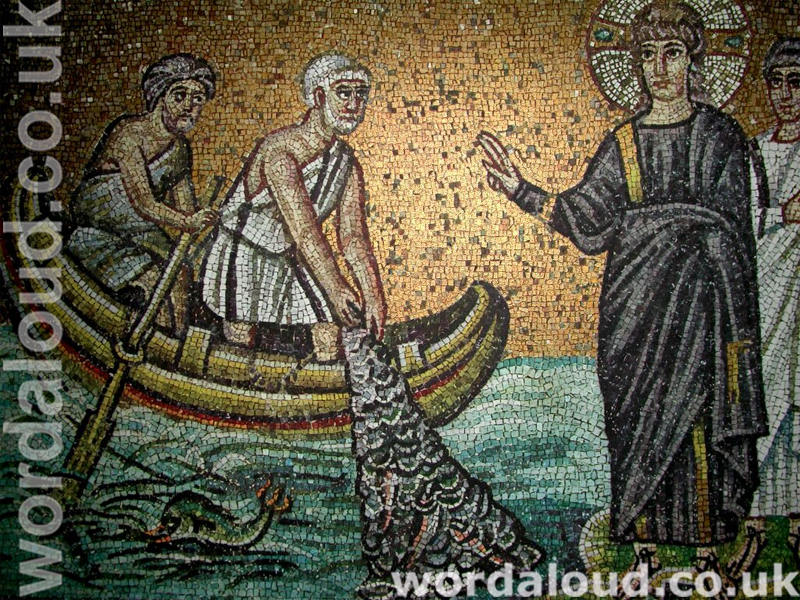

Christian Art | Boy At Prayer | Child With Jesus

Office Of Readings | Sunday, Lent Week 5 | From The Easter Letters Of Saint Athanasius | Jesus Is The Feast Of Easter | Jesus Is Both Priest And Sacrifice

‘We keep the Lord’s feast which is coming, not in words but in action.’

Christ As The Feast Itself

Saint Athanasius opens this Easter letter with a theological affirmation of Jesus Christ’s total and continuous presence among his people. Christ is not only the Redeemer and Teacher but becomes the very substance of the feast:

‘He has come among us as our feast and holy day as well.’

In this image, Athanasius collapses the categories of subject and object. Christ is not only the one who invites us to the feast; he is the feast. The sacrificial lamb, the priest who offers it, and the table at which it is shared—these are all fulfilled in the person of Jesus Christ. This theological density reflects Athanasius’ wider understanding of the Incarnation: that in Christ, God has assumed all dimensions of our reality to redeem them.

The Paschal Mystery And The Christian Life

The reference to Christ as the true Passover (cf. 1 Corinthians 5:7) anchors this reflection firmly in the Paschal Mystery. For Athanasius, the Christian feast is not a commemoration of a past event but a living participation in the death and resurrection of Christ. The liturgical celebration is thus inseparable from the moral and spiritual transformation of the believer. As he writes:

‘True joy, genuine festival, means the casting out of wickedness.’

Athanasius draws attention away from mere ritual observance and toward the ethical and contemplative demands of the feast. The one who would celebrate must first be purified—not merely ritually, but morally and spiritually.

This reflects the deep connection in the early Church between liturgy and ethics, a connection that is frequently obscured in modern practice. For Athanasius, you cannot keep the feast if you are not keeping the commandments.

Examples Of The Saints | Rejoicing Through Righteousness

To illustrate what such a celebration looks like, Athanasius invokes the figures of David, Moses, Samuel, and Elijah—those who, in the Old Testament, lived lives of worship and devotion. Their joy came not from external festivities but from lives dedicated to prayer, worship, and holiness. David rises seven times during the night to pray (cf. Psalm 119:164); Moses sings a hymn of deliverance at the Red Sea (Exodus 15); Elijah lives a life of radical fidelity to the covenant.

Athanasius positions these figures as precursors to Christian sanctity:

‘Because of their holy lives they gained freedom, and now keep festival in heaven.’

He presents them not only as historical examples but as models for Christian living in the present. Holiness is not decorative or optional—it is the prerequisite for celebration.

The Feast As Participation, Not Performance

As the letter continues, Athanasius deepens his exhortation. The celebration of the feast is not an external act but a movement of the whole self:

‘We keep his feast by deeds rather than by words.’

This aphorism crystallizes the pastoral thrust of the entire passage. Athanasius is not denigrating liturgical observance or doctrinal confession, but he is warning against their separation from the life of virtue. Keeping the feast ‘in truth’ means following Christ along the way of righteousness, humility, and charity.

He ties this to discipleship, quoting Christ’s words: ‘I am the way.’ The feast is not only something one enters into, but a way of life, marked by obedience and moral clarity. Lent, then, is the preparation not simply for liturgy but for transformation.

Purification Through The Word

In one of the more theologically rich moments of the letter, Athanasius draws a contrast between the ritual purification of the Old Testament and the spiritual cleansing offered by Christ:

‘In former times the blood of goats… purified only the body. Now… everyone is made abundantly clean.’

This evokes the argument of the Letter to the Hebrews (especially chapters 9–10), where Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice replaces the repeated sacrifices of the old covenant. Athanasius adds a specifically Alexandrian note: purification is not merely juridical or external—it is ontological. It changes the person from within. Christ, the Word of God, purifies through his grace and makes the soul fit for the contemplation of God.

Foretaste Of The Heavenly Jerusalem

Athanasius concludes with an eschatological vision:

‘If we follow Christ closely we shall be allowed, even on this earth, to stand as it were on the threshold of the heavenly Jerusalem.’

This echoes the already-but-not-yet dimension of Christian life. The heavenly liturgy, of which the Eucharist is a participation, is not only future but present. Insofar as the believer follows Christ through repentance, righteousness, and love, he or she already stands within the vestibule of eternal life.

From The Easter Letters Of Saint Athanasius

The Word who became all things for us is close to us, our Lord Jesus Christ who promises to remain with us always. He cries out, saying: ‘See, I am with you all the days of this age.’ He is himself the shepherd, the high priest, the way and the door, and has become all things at once for us. In the same way, he has come among us as our feast and holy day as well. The blessed Apostle says of him who was awaited: ‘Christ has been sacrificed as our Passover.’ It was Christ who shed his light on the psalmist as he prayed: ‘You are my joy, deliver me from those surrounding me.’ True joy, genuine festival, means the casting out of wickedness. To achieve this one must live a life of perfect goodness and, in the serenity of the fear of God, practise contemplation in one’s heart.

This was the way of the saints, who in their lifetime and at every stage of life rejoiced as at a feast. Blessed David, for example, not once but seven times rose at night to win God’s favour through prayer. The great Moses was full of joy as he sang God’s praises in hymns of victory for the defeat of Pharaoh and the oppressors of the Hebrew people. Others had hearts filled always with gladness as they performed their sacred duty of worship, like the great Samuel and the blessed Elijah. Because of their holy lives they gained freedom, and now keep festival in heaven. They rejoice after their pilgrimage in shadows, and now distinguish the reality from the promise.

When we celebrate the feast in our own day, what path are we to take? As we draw near to this feast, who is to be our guide? Beloved, it must be none other than the one whom you will address with me as our Lord Jesus Christ. He says: ‘I am the way.’ As blessed John tells us: it is Christ ‘who takes away the sin of the world.’ It is he who purifies our souls, as the prophet Jeremiah says: ‘Stand upon the ways; look and see which is the good path, and you will find in it the way of amendment for your souls.’

In former times the blood of goats and the ashes of a calf were sprinkled on those who were unclean, but they were able to purify only the body. Now through the grace of God’s Word everyone is made abundantly clean. If we follow Christ closely we shall be allowed, even on this earth, to stand as it were on the threshold of the heavenly Jerusalem, and enjoy the contemplation of that everlasting feast, like the blessed apostles, who in following the Saviour as their leader, showed, and still show, the way to obtain the same gift from God. They said: ‘See, we have left all things and followed you.’ We too follow the Lord, and we keep his feast by deeds rather than by words.