Christian Art | George Herbert | The Temple | Affliction (4)

George Herbert | The Temple | Affliction (4)

Broken in pieces all asunder,

Lord, hunt me not,

A thing forgot,

Once a poore creature, now a wonder,

A wonder tortur’d in the space

Betwixt this world and that of grace.

My thoughts are all a case of knives,

Wounding my heart

With scatter’d smart,

As watring pots give flowers their lives.

Nothing their furie can controll,

While they do wound and prick my soul.

All my attendants are at strife,

Quitting their place

Unto my face:

Nothing performs the task of life:

The elements are let loose to fight,

And while I live, trie out their right.

Oh help, my God! let not their plot

Kill them and me,

And also thee,

Who art my life: dissolve the knot,

As the sunne scatters by his light

All the rebellions of the night.

Then shall those powers, which work for grief,

Enter thy pay,

And day by day

Labour thy praise, and my relief,

With care and courage building me,

Till I reach heav’n, and much more thee.

![]()

George Herbert | The Temple | Affliction (4)

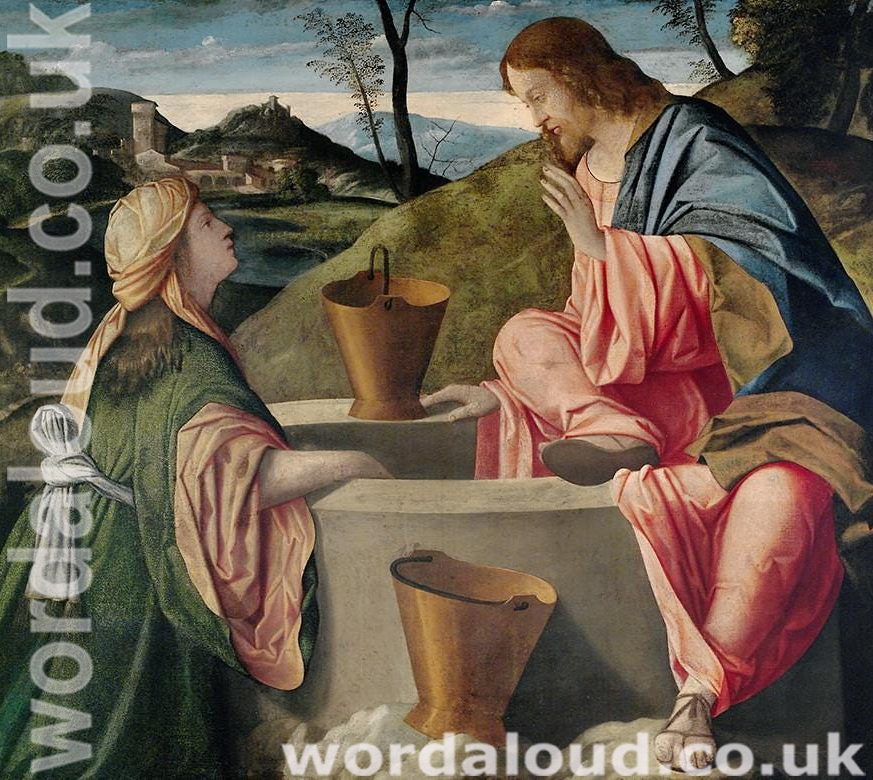

George Herbert’s Affliction (4) explores a personal and spiritual journey marked by expectation, suffering, and ultimate resignation to God’s will. The poem follows Herbert’s movement from early enthusiasm and joy in his relationship with God to a period of deep suffering and questioning, before finally arriving at a state of reluctant submission. The structure and language of the poem reflect the volatility of this experience, capturing shifts in mood and understanding as Herbert struggles with divine providence.

The opening stanzas establish a sense of spiritual optimism. Herbert recalls the beginning of his faith, when devotion to God seemed to bring fulfillment and a sense of purpose. He describes how he eagerly embraced religion, anticipating joy and security: ‘When first thou didst entice to thee my heart, / I thought the service brave.’ The word entice suggests an initial attraction to faith, as though Herbert were drawn in by its beauty and promise. He describes a time when God seemed to provide comfort, ensuring a life free from burdens: ‘Whereas my birth and spirit rather took / The way that takes the town.’ This suggests that he saw faith as a means of achieving victory and success in life, reinforcing the idea that he initially viewed religious devotion in transactional terms—he serves God, and in return, God provides rewards.

However, this early confidence quickly erodes. The tone shifts as Herbert describes a series of afflictions that challenge his expectations: ‘But as I did their sweetnesse still pursue, / I did begin to fret.’ The use of fret marks the beginning of his dissatisfaction. He encounters physical suffering, personal loss, and emotional turmoil: ‘Sicknesse with sinne did chase me / And made me to sit still.’ This shift represents the disillusionment that often follows an initial period of spiritual enthusiasm. Herbert had expected blessings, but instead he finds himself enduring trials that make him question the nature of divine love. The mention of sin as a force that accompanies sickness suggests that his suffering is not just physical but also spiritual—his affliction makes him doubt his own worthiness before God.

As the poem progresses, Herbert increasingly struggles with divine justice. He does not simply accept his suffering as part of a divine plan but questions why he has been made to endure it: ‘Now I am here, what thou wilt do with me / None of my books will show.’ This line signals a turning point in the poem—his previous knowledge, learning, and theological study provide no answers. Herbert is left in uncertainty, unable to rely on reason or doctrine to make sense of his pain. His frustration is compounded by a sense of betrayal: ‘Whereas my heart, once settled and at home, / Had no design but was entire with thee.’ He believed that full commitment to God would bring stability, but instead, his life has been shaken.

The final stanzas reveal a reluctant surrender to God’s will. Herbert does not receive answers or relief from his suffering, but he ultimately yields to divine authority: ‘Let me not love thee, if I love thee not.’ This paradoxical conclusion expresses the tension at the heart of the poem—Herbert recognizes that his devotion to God is incomplete, yet he also acknowledges that he cannot turn away. This closing line suggests a resigned commitment; he may not feel the joy and certainty he once had, but he knows that true faith does not depend on personal comfort.