Christian Art | George Herbert | Sepulchre | The Church | Frailtie

George Herbert | The Temple | The Church | Frailtie

Lord, in my silence how do I despise

What upon trust

Is styled honour, riches, or fair eyes;

But is fair dust!

I surname them guilded clay,

Deare earth, fine grasse or hay;

In all, I think my foot doth ever tread

Upon their head.

But when I view abroad both Regiments;

The worlds, and thine:

Thine clad with simplenesse, and sad events;

The other fine,

Full of glorie and gay weeds,

Brave language, braver deeds:

That which was dust before, doth quickly rise,

And prick mine eyes.

O brook not this, lest if what even now

My foot did tread,

Affront those joyes, wherewith thou didst endow,

And long since wed

My poore soul, ev’n sick of love:

It may a Babel prove

Commodious to conquer heav’n and thee

Planted in me

![]()

George Herbert | The Temple | The Church | Frailtie

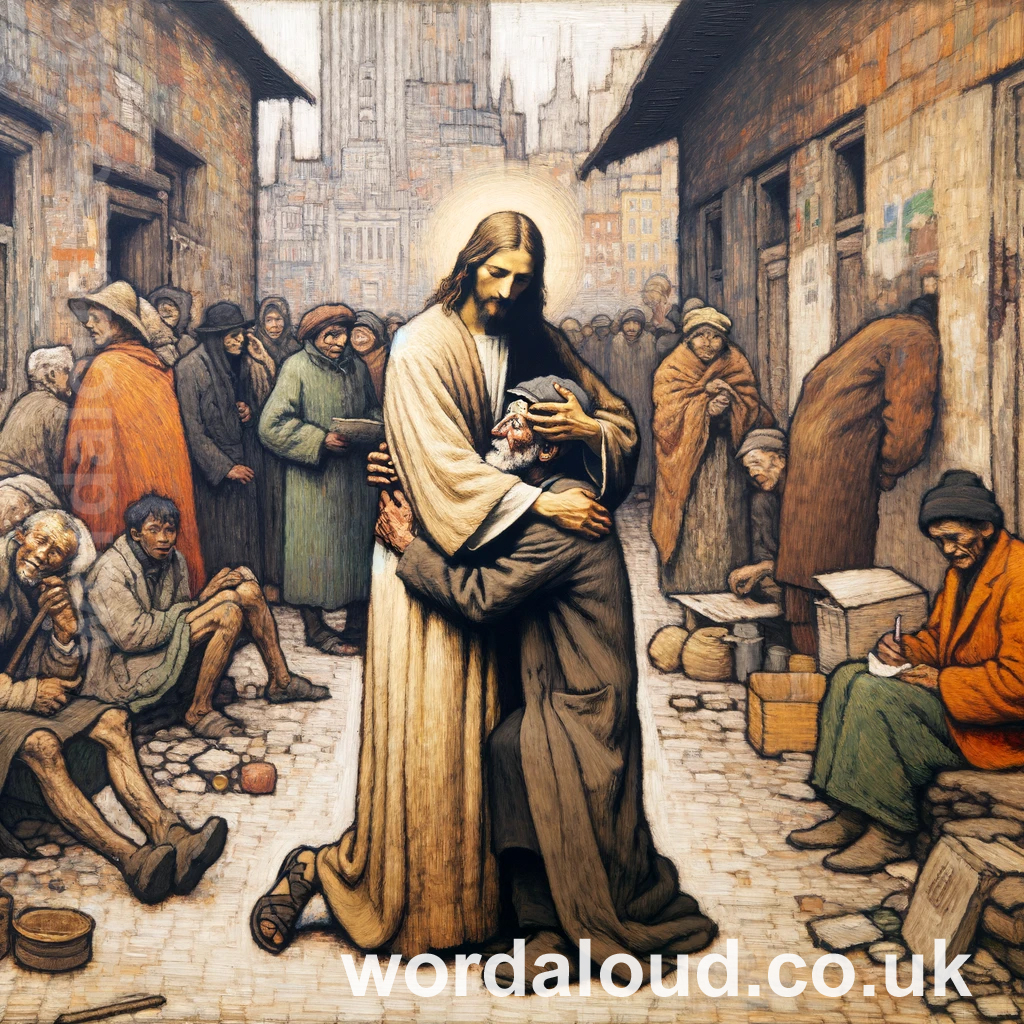

The poem is an introspective dialogue in which Herbert contemplates a tension between worldly values and divine realities. The poem opens with an expression of disdain for the superficial trappings of honour, wealth, and beauty. These are dismissed as transient, ‘fair dust’ that, despite their allure, amount to no more than ‘gilded clay’ or ‘fine grass or hay’. This imagery diminishes worldly achievements and possessions, positioning them beneath Herbert’s spiritual footing as something to be trodden upon rather than exalted.

However, Herbert’s view becomes unsettled when he contrasts ‘both regiments’, the world’s and God’s. The worldly regiment is characterized by outward splendour—’glory and gay weeds’, ‘brave language, braver deeds’. It dazzles with its ostentation, standing in sharp contrast to God’s regiment, described as ‘clad with simpleness, and sad events’. This juxtaposition creates an inner conflict for Herbert. Despite his earlier dismissal of worldly values, he acknowledges their capacity to ‘quickly rise, and prick mine eyes’. The phrase suggests that worldly allurements have a seductive power that can disturb spiritual clarity, provoking a sense of unease or distraction.

The final stanza addresses this internal struggle with a plea for divine intervention. Herbert warns against potential consequences of allowing worldly values to take root in his soul. He fears that such values, though initially trampled underfoot, might rise to challenge and ‘affront those joys’ granted by God, which have long been the foundation of his spiritual life. Reference to Babel evokes a biblical story of human hubris—an attempt to reach heaven through self-aggrandizement and ambition. Here, it serves as a metaphor for the spiritual danger posed by pride and attachment to worldly success.

The concluding lines suggest a vulnerability within Herbert. He recognizes that the temptation to align with worldly values could undermine his relationship with God, transforming his inner life into a ‘Babel’ rather than a sanctuary. Yet, the final plea implies a hope that divine grace will prevent this outcome, keeping Herbert grounded in spiritual truths rather than worldly illusions.

Throughout the poem, the use of dualistic imagery—earthly dust versus heavenly love, gay weeds versus sad events, Babel versus spiritual unity—underscores the dichotomy between the transient and the eternal. The poem’s movement from confidence to uncertainty reflects the complexity of spiritual struggle, as even a devoted soul can feel the pull of worldly attractions. Rhythm and structure mirror this tension, with shifts from assertive declarations to introspective self-doubt.

The poem’s theological underpinning suggests that true contentment and salvation lie in aligning oneself with divine simplicity rather than worldly grandeur. Herbert’s plea for vigilance and divine assistance highlights fragility of faith in the face of human ambition and pride. In this way, the poem serves as both a confession and a prayer, capturing a dynamic interplay of humility, temptation, and divine reliance in the spiritual life.