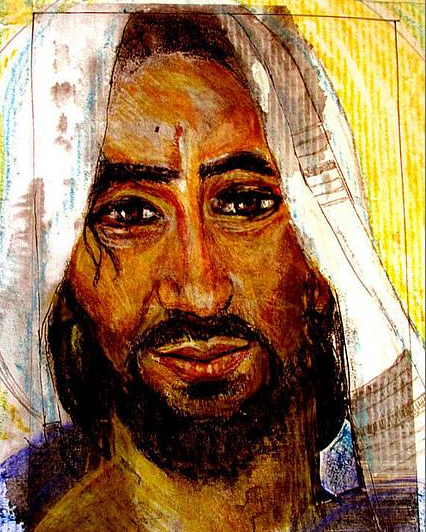

Christian Art | A Boy At Prayer With Jesus And The Trinity

Office Of Readings | Eastertide Week 4, Saturday | A Reading From The Commentary Of Saint Cyril Of Alexandria On The Letter To The Romans | All Are Saved Through Jesus | Opus Dei | Body Of Jesus Christ

‘God’s mercy reaches all men, and the whole world is saved.’

God’s Mercy Has Been Extended to All

This reflection, drawn from Saint Cyril of Alexandria’s commentary on the Letter to the Romans, richly develops the theological significance of unity, divine mercy, and the universality of salvation. The passage resonates deeply with themes central to Eastertide: renewal, reconciliation, and the triumph of divine love through the risen Christ. St Cyril, a towering figure in patristic theology and a staunch defender of orthodoxy at the Council of Ephesus, here offers a profound meditation on the body of Christ and the universal scope of redemption.

Unity In Jesus Christ | One Body From Many Members

Cyril opens with the Pauline image of the Church as the one body of Christ, comprised of many members (cf. Romans 12:4-5; 1 Corinthians 12:12). This ecclesial vision emphasises interdependence and mutual charity. The metaphor serves a dual function: it grounds Christian identity in relationality and reflects the Church’s calling to be a visible sign of unity amidst diversity. In Eastertide, this vision is especially poignant, as the risen Christ breathes peace upon his disciples and sends them forth as one body into a fragmented world.

Cyril underscores that this unity is not merely human cooperation, but something wrought by Christ himself: ‘Christ has made Jews and Gentiles one by breaking down the barrier that divided us.’ This directly evokes Ephesians 2:14, where Paul declares that Christ ‘is our peace’, having broken down the ‘dividing wall of hostility’. Cyril, writing in a context where the Church was consolidating its self-understanding post-Constantine and in the face of lingering sectarianism, insists on the supernatural foundation of unity. The Church is not a sociological club, but the mystical Body of Christ, reconciled through his flesh.

Mutual Responsibility And The Spirit Of Communion

‘If one member suffers some misfortune, all should suffer with him; if one member is honoured, all should be glad.’ This is a pastoral exhortation to lived solidarity, echoing Paul (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:26). In Cyril’s Christology, the Incarnation is not merely the descent of God into flesh, but the enfleshment of divine compassion. The Church, as the prolongation of Christ’s body in history, is called to embody that same compassion.

Here, Cyril aligns with the deep patristic intuition that salvation is not only individual but corporate. Unity is both gift and task. In our contemporary context of ecclesial fragmentation and social polarization, this ancient voice calls for a renewal of mutual empathy and shared mission.

Divine Mercy As The Basis Of Unity

Cyril’s reflection on the mercy of God is rooted in the Johannine proclamation: ‘God so loved the world that he gave his only Son.’ (John 3:16) He interprets this as both the source and the model of ecclesial communion. God accepted us in Christ—not conditionally, but freely, graciously, and universally. This acceptance becomes the blueprint for how Christians are to accept one another: ‘Accept one another as Christ accepted you, for the glory of God.’ (Romans 15:7)

By pointing to the divine initiative—’He has delivered us from death, redeemed us from death and from sin’—Cyril reinforces that unity and salvation are not human accomplishments but divine gifts. In this way, the theology of mercy becomes ecclesiology. The Church exists as the fruit and sign of God’s limitless compassion.

Christ As Servant And Fulfilment Of The Promise

Cyril skilfully weaves together Paul’s insights into Christ’s dual mission: to Israel and to the nations.

- Christ became a ‘servant of the circumcised’ to demonstrate God’s faithfulness to the patriarchal promises.

- Yet he also comes as the Redeemer of the Gentiles, expanding the covenant to the ends of the earth.

This twofold mission reflects the mystery of God’s plan (cf. Romans 15:8-9). It speaks to the continuity between the Old and New Testaments, showing that God’s mercy is not a new invention but the flowering of ancient fidelity. Cyril, steeped in the Alexandrian exegetical tradition, sees the Incarnation not as rupture but as fulfilment.

In contemporary theological discourse, this reinforces the importance of honouring the Jewish roots of the Christian faith while affirming the universal scope of salvation. It also supports a mission-centred ecclesiology, where evangelization is understood not as conquest but as participation in God’s ongoing work of reconciliation.

Mystery Of Salvation | God’s Wisdom And The Church

Cyril concludes with a meditation on the ‘mystery of the divine wisdom contained in Christ’, emphasizing that God’s salvific plan has not failed but triumphed. He notes that ‘in the place of those who fell away the whole world has been saved’.

This statement may refer to Paul’s teaching in Romans 11, where the failure of some within Israel to accept Christ becomes the occasion for the Gospel to go to the Gentiles. It is not a theology of replacement but of expansion and divine economy: what appears as failure in human eyes becomes the occasion for greater mercy.

Cyril’s affirmation that the ‘whole world has been saved’ must be understood in the context of universal availability of salvation, not automatic universalism. It reflects the Church’s Easter proclamation: that Christ’s victory over death is for all humanity, and that all are invited into the covenant of life.

Glossary of Terms

- Gentiles: A biblical term referring to all people who are not Jewish. In the New Testament context, Gentiles are those who were not part of the original covenant with Israel but are now included in salvation through Christ.

- Circumcised / Circumcision: In the Jewish tradition, circumcision is a physical sign of the covenant between God and Abraham. ‘The circumcised’ refers to Jewish people. Paul uses this term to speak of those under the old covenant.

- Divine Word: A title for Jesus Christ, especially in the Gospel of John, where He is identified as the eternal Word (Greek: Logos) who became flesh.

- Ransom: A theological term describing Jesus’ sacrificial death. It refers to the price paid to redeem or liberate humanity from sin and death.

- Patriarchs: The founding fathers of the Jewish people, particularly Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. God’s promises to them are seen as foundational to the story of salvation.

- The Law with its Precepts and Decrees: Refers to the Mosaic Law (Torah), including commandments and religious regulations given to Israel. According to Christian teaching, Jesus fulfilled and surpassed this law.

- Mystery of the Divine Wisdom: A phrase used by Paul and the early Church to describe God’s hidden plan for salvation, now revealed in Christ and extended to all peoples.

- One Body in Christ: A metaphor used by Paul to describe the unity of believers in the Church, where all members, though different, are united in Christ like parts of a single body.

- Unity of the Spirit in the Bond of Peace: A phrase from Ephesians 4:3 highlighting the spiritual unity among Christians, maintained through love, peace, and shared faith.

- Salvation: Deliverance from sin and death, made possible through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

- House of Israel: A biblical term referring to the Jewish people, the descendants of Jacob (also called Israel), to whom God’s original covenant was given.

- Redeemer: A title for Christ, highlighting His role in saving humanity from sin and restoring the relationship between God and man.

A Reading From The Commentary Of Saint Cyril Of Alexandria On The Letter To The Romans | All Are Saved Through Jesus

Though many, we are one body, and members one of another, united by Christ in the bonds of love. Christ has made Jews and Gentiles one by breaking down the barrier that divided us and abolishing the law with its precepts and decrees. This is why we should all be of one mind and if one member suffers some misfortune, all should suffer with him; if one member is honoured, all should be glad.

Paul says: Accept one another as Christ accepted you, for the glory of God. Now accepting one another means being willing to share one another’s thoughts and feelings, bearing one another’s burdens, and preserving the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. This is how God accepted us in Christ, for John’s testimony is true and he said that God the Father loved the world so much that he gave his own Son for us. God’s Son was given as a ransom for the lives of us all. He has delivered us from death, redeemed us from death and from sin.

Paul throws light on the purpose of God’s plan when he says that Christ became the servant of the circumcised to show God’s fidelity. God had promised the Jewish patriarchs that he would bless their offspring and make it as numerous as the stars of heaven. This is why the divine Word himself, who as God holds all creation in being and is the source of its well-being, appeared in the flesh and became man. He came into this world in human flesh not to be served, but, as he himself said, to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.

Christ declared that his coming in visible form was to fulfil the promise made to Israel. I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel, he said. Paul was perfectly correct, then, in saying that Christ became a servant of the circumcised in order to fulfil the promise made to the patriarchs and that God the Father had charged him with this task, as also with the task of bringing salvation to the Gentiles, so that they too might praise their Saviour and Redeemer as the Creator of the universe. In this way God’s mercy has been extended to all men, including the Gentiles, and it can be seen that the mystery of the divine wisdom contained in Christ has not failed in its benevolent purpose. In the place of those who fell away the whole world has been saved.